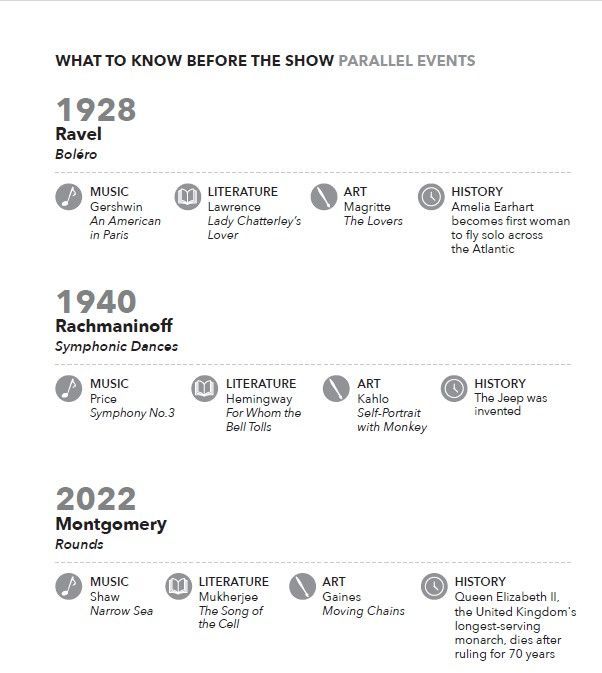

THE STORY BEHIND: Ravel's Boléro

Share

On February 14 & 15, conductor Anna Handler and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present BOLÉRO with pianist Awadagin Pratt.

Experimentation has always been a wellspring of creativity for composers. Great composers are rarely content to fall back on formulas that they've already proven to be successful, opting instead for a new approach or perspective that keeps the creative juices flowing. This is more than evident in the three bold pieces slated for performance this month.

Ravel himself called his Boléro "an experiment . . . consisting wholly of orchestral texture . . . one long, very gradual crescendo." And when the crescendo reaches its breaking point, Ravel makes a huge and unexpected harmonic leap. This immense build up and shock leave us breathless, realizing that we have just experienced what was once a radical challenge to the most basic assumptions of Western concert music.

Rachmaninoff, who had build his reputation on an unparalleled gift for romantic melodies, sly harmonies, saturated colors, and a penchant for the occasional Dies Irae, broke a compositional slump towards the end of his life to give us a decidedly modern treatment of these gifts. His Symphonic Dances, although originally intended for ballet, is today one of the greatest tours de force for orchestra. The result surprised even him. "I don't know how it happened," he remarked. "It must have been my last spark."

Jessie Montgomery is a name well known to Providence music lovers. She devoted her early career to performing and teaching for community organizations here, and any appearance of her music on a local concert stage is a cause for celebration. But this month's performance of Rounds is particularly special, as it was this work that earned her the 2024 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. Written specifically with this month's soloist, Awadagin Pratt, in mind, the work is an exploration of interconnectedness, using musical gestures to examine how seemingly opposites - such as darkness and light, swiftness and stagnation, tension and release - not only can but must coexist simultaneously.

Title: Boléro

Composer: Maurice Ravel

(1875-1937)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic:

Last performed April 11, 2015 with Larry Rachleff conducting. This piece is scored for piccolo, two flutes (second doubling piccolo), two oboes (second doubling oboe d'amore), English horn, two clarinets (second doubling E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, piccolo trumpet, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, two saxophones, timpani, percussion, harp, celesta and strings.

The Story:

"The piece I am working on will be so popular, even fruit peddlers will whistle it in the street." - Maurice Ravel

From the snare drum’s opening notes, even before the infamous melody begins, Ravel’s

Boléro

is instantly recognizable. Though originally intended for a ballet in 1928, it was quickly absorbed into popular culture, appearing in everything from films (10, Paradise Road, Boléro, Basic, and even the Three Stooges’

Soup to Nuts) to television (Doctor Who, Futurama), to rock and roll (Frank Zappa) to the Olympics (iconic ice dancers Torvill and Dean in 1984). It’s safe to say that Boléro wins the award for being the most seductive and influential composition “without music in it” (Ravel’s words).

Throughout its 15 minutes, two sultry, vaguely Spanish-Arabian tunes are repeated, with essentially no thematic development. Had someone suggested such an idea to Beethoven, he would have called it infantile. But Ravel’s genius comes through in his orchestration. While snare drums tap out a castanet-inspired rhythm that becomes a relentless, compulsive pulse, Ravel takes us on a tour through the entire orchestral ensemble, giving virtually every melodic instrument an opportunity to shed some new light on one of the themes. Along the way, Ravel gradually escalates both the volume and the tension until the music becomes seared into our brain.

What inspired such an unprecedented approach? Possibly a trip to America. Ravel, who loved machines, had a penchant for visiting factories. He loved the “wonderful symphony of travelling belts, whistles and terrific hammer blows which envelop you.” After one such visit in 1905, he remarked “How much music there is in all of this – and I certainly intend to use it.” Thirteen year later, having just received the commission for the ballet that was to become

Boléro, he was on a U.S. tour, and surprised his hosts with a request to tour the Ford factory in Detroit. It’s almost certain that the insistent, mechanical rhythms that surrounded him there rekindled the earlier spark. Regardless, there is no question that while the original Boléro dance finds its roots in 18th century Spain, Ravel’s groundbreaking masterwork could not have been written in any other century but the 20th.

Program Notes by Jamie Allen © 2024 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Tickets start at $20! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!