THE STORY BEHIND: Rachmaninoff's "Symphonic Dances"

Share

On February 14 & 15, conductor Anna Handler and the Rhode Island Philharmonic Orchestra will present BOLÉRO with pianist Awadagin Pratt.

Experimentation has always been a wellspring of creativity for composers. Great composers are rarely content to fall back on formulas that they've already proven to be successful, opting instead for a new approach or perspective that keeps the creative juices flowing. This is more than evident in the three bold pieces slated for performance this month.

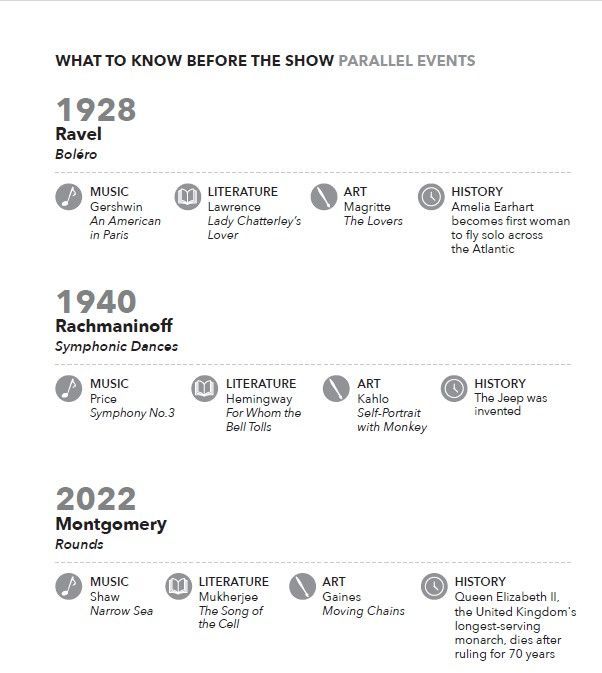

Ravel himself called his Boléro "an experiment . . . consisting wholly of orchestral texture . . . one long, very gradual crescendo." And when the crescendo reaches its breaking point, Ravel makes a huge and unexpected harmonic leap. This immense build up and shock leave us breathless, realizing that we have just experienced what was once a radical challenge to the most basic assumptions of Western concert music.

Rachmaninoff, who had build his reputation on an unparalleled gift for romantic melodies, sly harmonies, saturated colors, and a penchant for the occasional Dies Irae, broke a compositional slump towards the end of his life to give us a decidedly modern treatment of these gifts. His Symphonic Dances, although originally intended for ballet, is today one of the greatest tours de force for orchestra. The result surprised even him. "I don't know how it happened," he remarked. "It must have been my last spark."

Jessie Montgomery is a name well known to Providence music lovers. She devoted her early career to performing and teaching for community organizations here, and any appearance of her music on a local concert stage is a cause for celebration. But this month's performance of Rounds is particularly special, as it was this work that earned her the 2024 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. Written specifically with this month's soloist, Awadagin Pratt, in mind, the work is an exploration of interconnectedness, using musical gestures to examine how seemingly opposites - such as darkness and light, swiftness and stagnation, tension and release - not only can but must coexist simultaneously.

Title: Symphonic Dances

Composer: Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Last time performed by the Rhode Island Philharmonic: Last performed March 21, 2015 with Larry Rachleff conducting. This piece is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, alto saxophone, timpani, percussion, harp, piano and strings.

The Story: Rachmaninoff loved dance. He had dreamt of composing a ballet for the choreographer Michel Fokine (of Les Sylphides, The Firebird, and Petrushka fame) for much of his life, but unfortunately nothing ever came of his early efforts in the realm. Fokine’s first choreography to the music of his friend was, in fact, not a ballet at all, but an interpretation of his popular Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, presented in 1939 at Covent Garden under the title Paganini, at which time Rachmaninoff had seemed to stop composing altogether. But in the summer of 1940, the composer found himself in an ideal situation to put pen to manuscript paper once again. He and his family had rented an estate in Long Island, where good friends (including the Fokines, Vladimir and Wanda Horowitz, his former secretary Evgeny Somov, and Alexander Greiner of the Steinway company) lived nearby. There was enough space to allow him to compose undisturbed, which he often did from dawn to till dusk. By August of that year, Rachmaninoff wrote to Eugene Ormandy, the newly minted conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, with which he had already developed a long working relationship: “Last week I finished a new symphonic piece, which I naturally want to give first to you and your orchestra. It is called Fantastic Dances. I shall now begin the orchestration [….] I should be very glad if you would drop over to our place. I should like to play the piece for you.” But he was equally excited by the prospect of sharing the new work with Michel Fokine, in hopes of a second collaboration. Tragically, Fokine died before a second collaboration could take place, and Rachmaninoff mourned not only for a friend, compatriot, and fellow artist, but for an unrealized work as well.

The orchestral premiere of what was now called Symphonic Dances took place in Philadelphia in 1941, to great public acclaim. While a bit more conservative than much of his earlier work, there is still an originality and force of expression that is quintessentially Rachmaninoff here.

The first movement bears the unusual marking of “Non allegro” (not cheerful), and starts with a sinister sounding march. Listen for the ingenious dovetailing of woodwind duets and trios, and particularly the aching saxophone solo. In a surprising move towards the end, Rachmaninoff calls on the piano, harp, glockenspiel, flute, and piccolo to lift the music into a more joyous realm, retaining a playful sparkle until the movement’s close. His creative manipulation of orchestral colors continues in the second movement waltz, placing the listener within a musical house of mirrors that leads inevitably into the dizzying tapestry that is the work’s finale. Here we find dark forces, such as the Gregorian

Dies Irae melody from the Mass for the Dead and

danses macabres in the strings, which Rachmaninoff vanquishes with triumphant melodies stolen from his own

All-Night Vigil of many years earlier. The result leaves the listener both thrilled and breathless.

Program Notes by Jamie Allen © 2024 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Tickets start at $20! Click HERE or call 401-248-7000 to purchase today!