Learn the story behind Bramwell Tovey’s inaugural concert, Sept. 28

Share

Pianist Bronfman performs

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.3

The season opener features Grammy-winning pianist Yefim Bronfman and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.3, which is known as one of the most challenging pieces of classical music to perform. Tovey and the Orchestra will also perform Bartók’s popular Concerto for Orchestra.

The TACO Classical concert is at 8 p.m., Saturday, Sept. 28, at The VETS

Piano Concerto No.3 in D Minor, Op.30

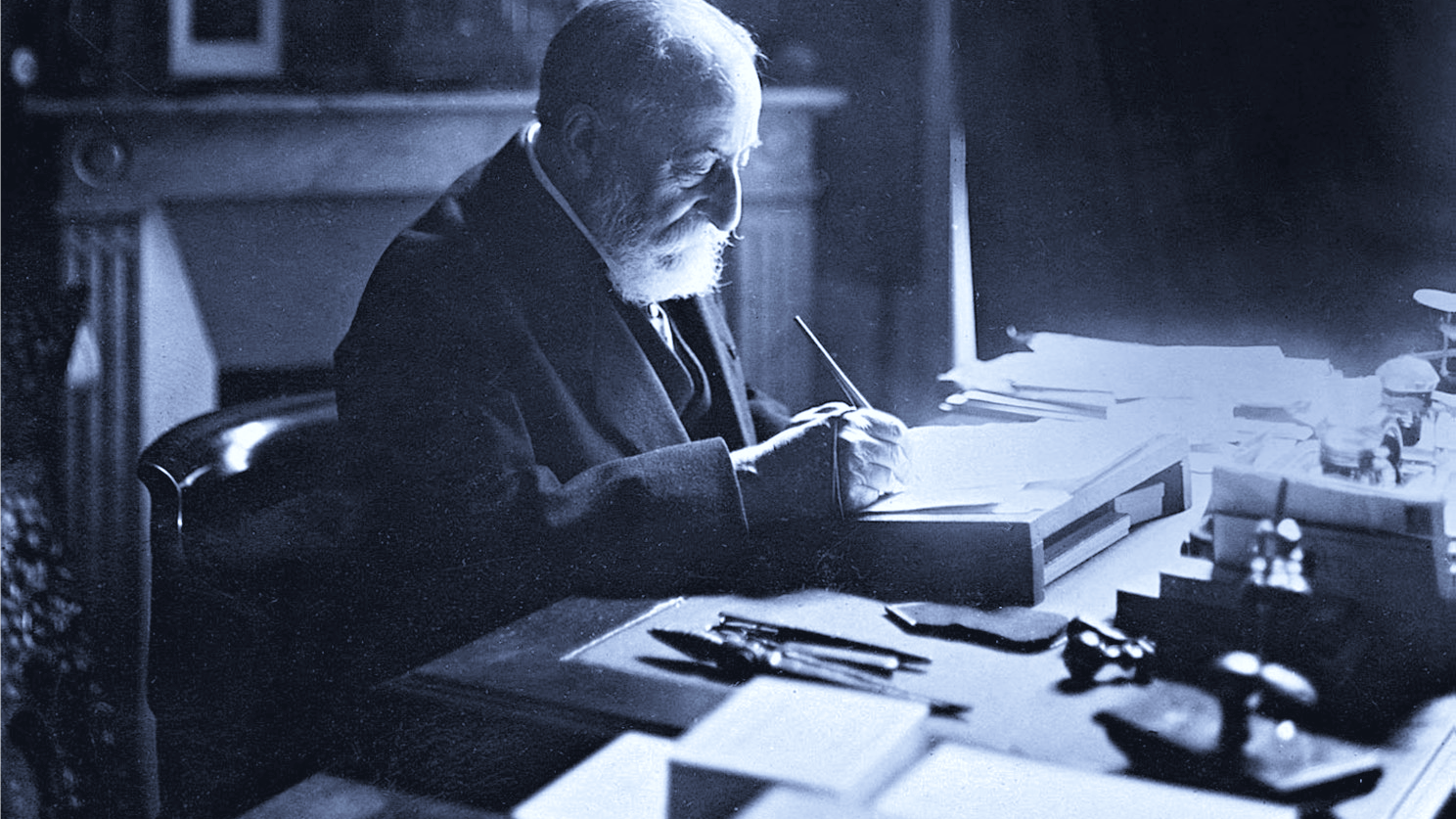

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF (1873-1943)

The composition of Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto in 1909 is mysterious. The composer made no mention of it in his writings until much later, and his family did not even know he was composing the work until it was finished. This situation could have been due to the concerto’s connection with Rachmaninoff’s dreaded upcoming tour of the United States. As the time of the tour approached, he hated the idea more and more, but he had a contract that could not be broken. As it turned out, the tour was a success. Rachmaninoff premiered the D Minor Concerto in New York in November 1909 with Walter Damrosch conducting. He played it in several other cities, then repeated it in New York the following January, this time under the baton of Gustav Mahler.

Because of the concerto’s difficult and unrelenting solo part, no other pianist would touch it for a long time, not even the great Joseph Hofmann to whom the work was dedicated. During the 1930s, Vladimir Horowitz became the first to play it regularly. Then pianists of the next generation, such as Emil Gilels and Leonard Pennario, performed and recorded the concerto, firmly establishing its popularity and place in the repertoire.

In a 1935 letter to Joseph Yasser, Rachmaninoff remarked of the first movement’s main theme, “It simply wrote itself. If I had any plan in composing this theme, I was thinking only of sound. I wanted to sing the melody on the piano, as a singer would sing it… .” This long-breathed theme is the most important one in the concerto, since parts of it return, transformed, in each of the movements. The second theme begins as a rhythmic dialogue between piano and orchestra, but soon evolves into a sweeping and lyrical expression like the main theme. Following a passionate development comes an even more passionate piano cadenza. The orchestra makes its presence felt little by little until a brief restatement of both themes in the movement’s ending.

The adagio movement is titled intermezzo. An elegiac mood in the orchestral opening breaks off suddenly with the soloist’s entrance. Following the sumptuous first section comes a spirited scherzando middle section for piano and pizzicato strings on a melody clearly derived from the first movement’s main theme. The intermezzo leads directly to the finale. The principal theme here is like a Russian dance, as brilliant and rhythmically driving as any by Tchaikovsky or Prokofiev. Episodes of varying character and tempo alternate with this theme. As a conclusion, Rachmaninoff creates increasing rhythmic excitement by incrementing the tempo to vivace, vivacissimo and finally a blazing presto to form the ending.

Concerto for Orchestra

BÉLA BARTÓK (1881–1945)

“The title of this symphony-like orchestral work is explained by its tendency to treat the single orchestral instruments in a concertante or soloistic manner… .” With these words, printed in the program of the December 1944 premiere, Béla Bartók introduced the world to his Concerto for Orchestra, destined to become his best-known music and one of the 20th century’s great symphonic masterpieces. It is a work exemplary of Bartók’s most mature style and of his classic tendencies. Bartók used the word concertante, the 18th-century practice of featuring instruments of the ensemble soloistically, singly or in small groups. His five-movement plan likewise reflects the Classic-period symmetry of the divertimento, with a slow movement surrounded by two quicker movements (II and IV), which are in turn surrounded by an Introduction and a Finale.

Individually, too, the movements bear 18th-century features. The first movement, for example, is a modified sonata form. The slow introductory passage gradually discovers the energetic, thrusting first theme. The oboe and harp introduce the lyrical second theme. In the development, the novelty is the pair of fugue-like passages for brass—on a theme and on its inversion—that climaxes the section and lead to the abbreviated recapitulation.

“Game of Pairs” is the title of the gentle, scherzo-like second movement, which features like instruments in pairs. In turn we hear the bassoons, oboes, clarinets, flutes and trumpets, each pair with its own distinctive and idiomatic theme punctuated by the strings. The contrasting brass chorale in the central section bridges into an enhanced reprise of the entire first section.

The third movement, Elegy, is one of Bartók’s atmospheric, nocturnal pieces that biographer Halsey Stevens has dubbed “night music.” The reappearance of material from the opening of the first movement provides what Bartók called “the core of the movement, which is enframed by a misty texture of rudimentary motifs.”

A second gentle scherzo, the fourth movement, comes in the form of an Interrupted Intermezzo. In it, two themes alternate. Before the final statements, comes an interruption: the burlesque of a theme from Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony that Bartók had found ludicrous.

The highly energetic Finale puts the strings at the concertante forefront. As in the finales of classic symphonies (and many Bartók works), a dance impulse takes charge of the rhythm. Suddenly, a fugue-like passage breaks out in the woodwinds, only to be quelled by a more tranquil tempo. Egged on by the strings, the tempo picks up again, and then a real fugue, the central section of the Finale, unfolds spontaneously. We hear its theme in a variety of shapes and characters passed between sections like the subject of a symposium. Again, the strings clamor for attention, beginning a recap of their rushing opening section. This time, however, the perpetual motion cannot be stopped, and the recap turns, except for a short breather, into an exciting, steamroller coda.

***At a Glance ***

Bramwell Tovey Inaugural: Bronfman Plays Rachmaninoff

Sept. 28, 8 p.m.

The VETS, One Avenue of the Arts, Providence

Bramwell Tovey, conductor

Yefim Bronfman, pianist

Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No.3

Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra

BUY TICKETS

Tickets start at $15 (including all fees), and can be purchased online at tickets.riphil.org, in person from the RI Philharmonic Orchestra Box Office in East Providence, or by phone 401.248.7000 (Mon.-Fri. 9 a.m.-4:30 p.m.). On day of concerts only, tickets are also available at The VETS Box Office (Friday, 3:30 p.m.–showtime; Saturday, 4 p.m.-showtime). Discounts are available for groups of 10 or more. Questions can be emailed to boxoffice@riphil.org.